A Judge on Trial

Before Twitter and cable news, political fights were up close and personal. For John Becker LLB1890, the battle that would change the course of his life took place 100 years ago on a February night in Monroe, Wisconsin, at the height of World War I.

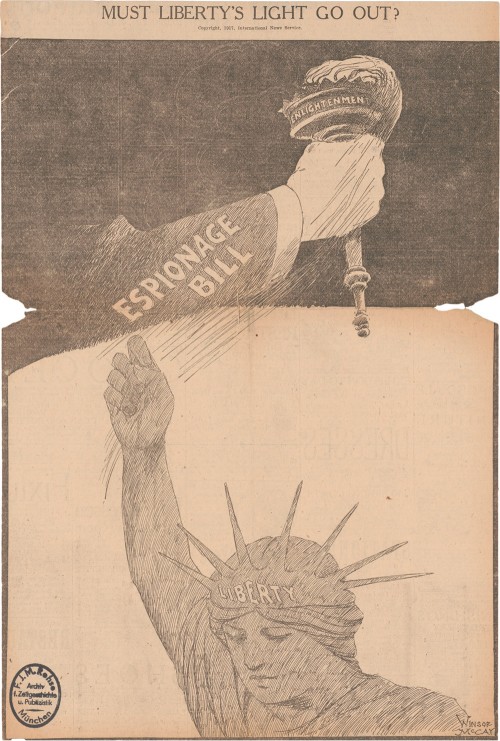

This editorial cartoon opposing the Espionage Act was published before Congress passed the law in June 1917. Federal prosecutors used the act to charge Becker less than a year later. Winsor McCay, Library of Congress; Green County Clerk of Courts

It was 17 degrees below zero outside when the shouting started inside the courthouse. Becker, a local judge, was among 50 or so residents who trudged through two feet of snow in the howling wind to attend a regularly scheduled meeting of the Green County Board. Not enough board members made the journey, so without a quorum, the group left county business aside. An informal and increasingly agitated conversation about the war erupted. Becker did not back down.

“There is no shortage of food. The idea of a shortage of food is being preached by agents employed by corporations for their own gains and going about the country on high-paid salaries,” said Becker, an ardent pacifist and Progressive Republican gubernatorial candidate. “This is a rich man’s war. There is no labor shortage. There is no seed shortage. Farmers, beware of taxes, war taxes, which must be paid in July.”

“I have listened to a speech which is seditious,” responded Monroe school superintendent Paul Neverman with indignation. “If the boys over in France could have heard his speech, they would make short work of him.”

“I doubt you can define the word seditious,” Becker replied.

“You’re a traitor,” the superintendent sneered.

Roughly three and a half months later, Albert Wolfe LLB1900, the U.S. Attorney for Western Wisconsin, made the accusation official.

In a 12-page indictment, he accused Becker of violating the Espionage Act of 1917. He charged him with seven counts of making false statements “willfully and feloniously … with the intent to interfere with the operation and success of the military and naval forces of the United States.”

“This is a rich man’s war,” said Becker, a Wisconsin judge who questioned U.S. involvement in World War I.

Becker was no stranger to challenging the government: he believed it was the definition of what citizens should do. He was the chair of Wisconsin’s Commission on Peace and lobbied for a citywide referendum in Monroe on whether the United States should get involved in World War I. In April 1917, three days before the U.S. entered the war, Becker and his fellow Monroe neighbors voted 954 to 50 against American intervention in the conflict.

The Milwaukee Journal called the referendum, “The Monroe Folly,” and wrote that the “stupidity and disloyalty” of the city injured the whole state. And the Los Angeles Times editorialized that there was “more disloyalty per square foot in Wisconsin than anywhere else in the country.”

But once U.S. soldiers headed to Europe, Becker encouraged his son to sign up for the military and stated publicly it was the responsibility of all citizens to support the war effort. At the same time, he poked and prodded at elected officials, as did his political mentor, Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette 1879, to ensure a more representative policy.

“Judge Becker practiced a complex patriotism, not unlike that of Senator La Follette,” says Richard Pifer MA’76, PhD’83, who recently authored The Great War Comes to Wisconsin: Sacrifice, Patriotism, and Free Speech in a Time of Crisis. “He approached the war effort with similar integrity and nuance, advocating policies he thought best for the nation during the war, even when his position flew in the face of government policy, and even though the result would lead to hostile attacks by super-patriots with little understanding of the war or Judge Becker.”

Those “super-patriots” took Judge Becker to trial in August 1918. A jury took less than six hours to convict him and he was sentenced to three years at the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. Wolfe, the U.S. attorney, told reporters afterward that he hoped Becker’s situation would “deter” lesser citizens who might be disloyal. Becker was forced to resign the seat on the bench he’d been elected to five times and held for 21 years in his community.

“It seemed to me, the response to what he said was over the top,” says Leslie Bellais MA’09, curator of social history at the Wisconsin Historical Museum. “It was an ongoing struggle in America, balancing civil liberties with national security. We saw it all over the United States and especially in Wisconsin — this overwhelming desire to shut down civil rights — a reaction, as we would see it today, that seemed un-American.”

The museum displays a sign donated by Becker’s family members that someone affixed to their home during his 1918 trial. Below his name is a crudely drawn figure in yellow with a speech balloon that says, “Berlin for Me.”

“It’s a powerful statement that during World War I, people would attack others this way,” Bellais said. “It’s not an abstract concept. This impacted real people.”

Becker never served a day in jail, and the U.S. Court of Appeals overturned his conviction two years later, but the court of public opinion had rendered its verdict. He was defeated in his subsequent attempts to run for district attorney and for his former county judge seat.

When he died in 1926 at age 57, the local newspaper in Monroe described him as “a fighter, but fair. If he felt he was right, he battled to the end, staunchly supporting his friend, client, or cause upon which he was engaged and if defeated … winning admiration even of those opposed to him at the time.”

Adam Schrager is a journalist at WISC-TV in Madison.

Published in the Spring 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.