How to Fix a Broken Police Department

Reforms were slow to take hold in Cincinnati, but when they did, they drove down crime while also reducing arrests.

CINCINNATI—Citizens were throwing stones and beer bottles at police officers in front of City Hall, and Maris Herold didn’t understand what they wanted.

She was a police officer herself, and knew that her department had made some missteps. Most recently, an officer gunned down a 19-year-old unarmed black man, Timothy Thomas—the fifteenth black man to die at the hands of police in five years.

But, Herold knew, the police were investigating the incident. They were listening to the community. They were working 12-hour shifts to protect the city from looting and fires, though the disturbance would soon turn into the worst riots in the U.S. in a decade.

“I was like, ‘We’re doing everything right, obviously the police officers made mistakes and we’re trying to get to the bottom of it,’” she told me recently. Herold, who joined the police force after a career in social work, couldn’t understand what more the police could do to make amends with the community.

That was in 2001. “In the police department, we thought we had great relationships with the majority of our communities,” Tom Streicher, who was police chief from 1999 to 2011, told me. “The reality was that we found out we had superficial relationships.”

Herold now sees how little she understood about policing, transparency, and the community back then. She’s now a District Commander in the Cincinnati Police Department, where more than a decade of negotiations have led to significant reforms. Herold believes that the changes made in the department are the best way to guarantee a good relationship between a city and its police force.

“I had all of these things running through my mind, but I had only half the picture at that point,” she told me.

It took a long time for Cincinnati police to get the other half of the picture. The public commitment to reform came in the immediate aftermath of the riots, but five years elapsed before the police started making meaningful changes. Though they were required by the Justice Department to reform their procedures, police still chafed at being told to fix a problem they didn’t think existed. Even now, police reform in Cincinnati remains a delicate issue. The various stakeholders, including the African American community, elected officials, civil-rights lawyers and law-enforcement leaders, constantly discuss and evaluate their progress. As part of the reforms, police agreed to adopt a strategy that required them to interact frequently with members of the community, and continually re-affirmed their commitment to that strategy.

The city that once served as a prime example of broken policing now stands as a model of effective reform. Cincinnati’s lessons seem newly relevant as officials call for police reform in the aftermath of the deaths of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Michael Brown in Ferguson and Tamir Rice in Cleveland. Indeed, the recently released report from President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing recommends that departments adopt some of the strategies used by Cincinnati. A task force convened by Ohio Governor John Kasich cited Cincinnati as a model for community-oriented policing and recommended that other law-enforcement agencies in that state develop similar reforms.

And on Tuesday, when the Justice Department and the city of Cleveland announced they’d entered into an agreement over how to resolve policing problems, their consent decree looked very similar to what had been drawn up in Cincinnati. Both documents stress the need for deep community involvement in policing as part of the reforms.

“The central component is the community policing,” Cleveland Police Chief Calvin Williams said at a news conference Tuesday. “If we don’t ensure that our officers and our community have a better relationship, then a lot of what we’re trying to implement now in terms of this agreement is going to be hard to do.”

But the lessons of Cincinnati are complicated. Success required not just the adoption of a new method of policing, but also sustained pressure from federal officials, active support by the mayor, and the participation of local communities. If Cincinnati is a model of reform, then it is equally a sobering reminder of how difficult it can be to change entrenched systems.

* * *

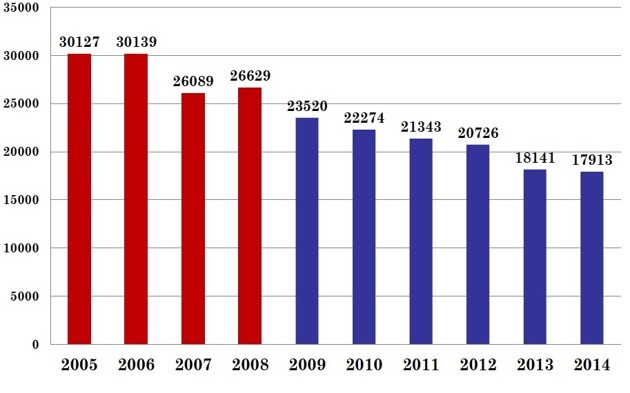

Looking back, the results of Cincinnati’s reform efforts are startling. Between 1999 and 2014, Cincinnati saw a 69 percent reduction in police use-of-force incidents, a 42 percent reduction in citizen complaints and a 56 percent reduction in citizen injuries during encounters with police, according to a report by Robin S. Engel and M. Murat Ozer of the Institute of Crime Science at the University of Cincinnati. Violent crimes dropped from a high of 4,137 in the year after the riots, to 2,352 last year. Misdemeanor arrests dropped from 41,708 in 2000 to 17,913 last year.

Yet it might not be so simple to adopt Cincinnati’s changes in other cities. It took a long time—five to ten years, by some counts—to get police to actually buy into the reforms. Nobody likes it when somebody comes into their workplace and tells them how to do their job. The changes Cincinnati adopted were nothing short of a complete turnaround in how the city approached incarceration, crime and its relationship with its residents. And to make sure they were adopted, the federal government had to apply constant pressure, reminding all parties involved about the need to stay vigilant about reform.

“In the early 2000s and late 90s, Cincinnati was just a hotbed of problems, and we got the city and the police department to agree to certain reforms,” said Mike Brickner, senior policy director with the ACLU of Ohio, which sued the city shortly before the riots over discriminatory policing practices. “It’s gratifying for me to see that people are coming back several years later and recognizing how successful it was.”

Some of the changes were small: The police department vowed to hold a press conference within 12 hours of any officer-involved shooting and to provide information as well as camera footage from the event. It agreed to track officers who received an inordinate number of complaints or who violated policies, and take disciplinary action if needed. It established a Citizen Complaint Authority with investigative and subpoena powers over police. It adopted new use-of-force policies, changed guidelines on when to use chemical spray, and established a mental-health response team to deal with incidents in which a suspect may have mental-health problems.

But those changes were tiny in contrast to what Herold and others say completely altered the department over the course of a decade: the adoption of a new strategy for how to police. The settlement agreement for the ACLU lawsuit, dubbed the Collaborative, required Cincinnati police to adopt community problem-oriented policing, or CPOP. The strategy required them to do fewer out-and-out arrests, and instead focus on solving the problems that cause people to commit crimes in the first place.

The Cincinnati model lowers incarceration rates and crime rates, advocates say, and makes for a much better relationship between city residents and police. Though the city was only required to adopt the strategy for five years, police have constantly re-affirmed their commitment to it, and still attend meetings every six weeks to update the community on their progress.

“There are lots of different strategies that don’t rely on arresting black people and feeding more mass incarceration, and that’s what we’ve worked so hard on,” said Al Gerhardstein, the lawyer who sued the city for the ACLU (and who was also the lead counsel in the latest gay marriage case in front of the Supreme Court). “I think it really worked. For years, our police officers have become real fans of the Collaborative, they like problem solving. They like solving the underlying reasons of the crimes.”

Even those who constantly worry that policing in Cincinnati will some day revert back to the old ways of doing things say that other cities need to learn from Cincinnati. They include Iris Roley, a community activist who was an integral part of the Collaborative and who traveled to Ferguson last year to distribute copies of the Collaborative, hoping to suggest a way forward.

“I think where we are in 2015 is that every police municipality needs to take a look at itself, and wherever it can, change and institute community-driven, focused reforms,” she told me.

* * *

There were certain things that were expected of Maris Herold when she first became a cop. She was expected to write a few traffic tickets a month, issue some parking tickets, and get a misdemeanor arrest, a felony arrest, and a DUI arrest. If police were out making arrests, the thinking went, they were proactively preventing crime. So Herold followed the guidelines, got positive evaluations, and was seen by supervisors as a good cop.

Even before the riots, though, community members could see that this approach wasn’t working. The strategy made police see the public as people who could, at any moment, be committing crimes. The effort to prevent crime led police to arrest all sorts of innocent people, souring the relationship between law enforcement and the community.

“What we did horribly wrong was we engaged in zero tolerance sweeps—that was our primary response when we'd have flare-ups in neighborhoods,” Herold told me. “That, I think, stretched any foundation that we had built with the community.”

A month before the riots, the ACLU and the Black United Front sued the city, alleging that police participated in racial profiling and discriminatory law enforcement. Some of the complaints about the police department seem eerily similar to those being leveled against other police departments today. There was the man who was tackled and arrested and died of asphyxiation in police custody. The mentally ill man who was shot by police after waving a brick in the air. The man whom police shot after pulling him over, although witnesses said he was not behaving erratically.

For a community already suspicious of police, the shooting of Timothy Thomas in April of 2001 was the last straw. The 19-year-old, who was wanted on 14 warrants, ran from police, according to the officer who shot him. That officer also claimed that Thomas did not respond to an order to show his hands. When community members marched to City Hall to protest the shooting, the City Council and the police had few answers for them. The crowd poured out into the streets, kicking off five days of clashes between residents and police, and bringing the nation’s attention to Cincinnati.

The scope of that civil unrest convinced many people in the city that it wouldn’t be possible—or wise—to just settle the lawsuit and going on with policing as it had been done. The mayor asked the Department of Justice to review the police department’s use-of-force policy, and the Department of Justice then opened a “pattern or practice” inquiry.

After months of negotiations, the Department of Justice entered into a Memorandum of Agreement with the city and the police, requiring the police department to make a number of changes in how it conducted business. Even more importantly, to settle the lawsuits, the city, the police union, and the plaintiffs (represented by the ACLU and the Black United Front) entered into a separate agreement, called the Collaborative. It required that police use community problem-oriented policing and laid out metrics for how they would be held accountable for adopting it.

That broke with precedent. Department of Justice consent decrees typically involve the city and the federal government, but the Collaborative also brought in the community and the police union. And it also attempted to change not just specific practices, but the city’s entire approach to policing. The final report issued by the city’s independent monitor, Saul Green, stressed the novelty of this approach to police reform:

Justice Department agreements typically do not attempt to directly address policing strategies used by the department under investigation. The differences are so significant that the Monitor Team believed from the start that if the Cincinnati effort proved successful, Cincinnati could serve as an important model for police reform throughout the United States.

Problem-oriented policing was developed in 1979 by Herman Goldstein, a University of Wisconsin professor, and was first adopted in Newport News, Virginia. Other police departments, such as Baltimore, have used the method and then abandoned it, said John Eck, a criminologist at the University of Cincinnati who helped the city adopt problem-oriented policing (which it calls Community Problem-Oriented Policing). The strategy suggests that police should not just respond to calls for service. It says they should also look for patterns in these calls to service, determine what is causing the patterns and then implement solutions to solve them, he said.

If hospitals notice an inordinate number of emergency patients coming in with facial injuries due to glass beer bottles being broken over their heads in fights, as was the case in on British precinct, police work with the bottle manufacturer to make bottles are made out of material that won’t break, he said. If police notice a women is a repeat victim of domestic violence because her partner breaks into her ground-floor apartment, they work with the landlord to move her to a higher floor, link her to a social-services agency and help her find free daycare so she doesn’t have to rely on her abusive spouse for help. In another example, when police noticed an increase in metal thefts in a neighborhood, they worked with property owners to paint their copper pipes green, posted signs about the pipes being painted green and then informed scrap yards of the program to gain support, which led to a reduction in copper thefts.

The strategy requires that police intimately know members of the community and listen to their concerns, even if doing so doesn’t lead to arrests. It requires that they get out of their cars and walk the streets, and it requires that they reach out to partners they traditionally would battle, such as the owners of buildings in high-crime spots, or community groups like Legal Aid.

New policing approaches come and go, seemingly every year, but leaders such as Herold say that problem-oriented policing differs in important ways from other strategies. Broken-windows policing, for example, holds that police can prevent bigger crimes by cracking down on disorder and small crimes in a neighborhood. But law-enforcement officers often end up just making a lot of arrests with broken-windows policing, instead of addressing the problems that lead to small or big crimes in the first place.

Similarly, Compstat, which was pioneered in New York City in the 1990s, uses statistics and mapping to identify crime patterns and direct resources there. It’s been credited with lowering crime in New York City, but also criticized by some criminologists for focusing on the numbers of arrests different officers make, rather than on protecting residents with the help of community input.

Hot-spots policing uses data to deploy officers to areas where crime and disorder are concentrated, but its effects are usually short-term because the approach rarely focuses on the causes of the crime, Eck said.

“Most cops, in any organization, have seen the reform du jour come through, and it varies from wearing your hats in a certain way to something more sophisticated,” Eck told me. “Police chiefs come, polices chiefs go, just as dumb ideas come, dumb ideas go.”

When I asked Eck how he knew that problem-oriented policing, which is also called problem-solving, isn’t just another fad, he admitted that sometimes he wonders the same thing. But when he tries to think of an alternative, he always comes back to the fact that unlike Compstat or other approaches, problem-solving deals with the complexity of what’s going on in a community. The police department, he says, is the only government institution that has a strong hierarchy and works around the clock, and so it can most effectively marshal resources and other departments to solve difficult problems.

Recent criticisms of police have focused on how conscious and unconscious biases may influence the ways in which individual officers act. But problem-oriented policing is also the best approach to reducing biases, Eck said, because it forces police to interact constantly with different members of the community.

“Whenever we come to a situation with a particular bias, that bias gets facilitated by lack of human contact,” he said. “The more you get police directly engaged with members of the public, the better it is.”

Still, no matter the policing approach leaders are trying to implement, officers are often skeptical that an outsider can really tell them the best way to do their job.

It’s a natural human reaction to being criticized so publicly by people who don’t actually have to do policing.

“It’s as if someone would come into your household and say, ‘You are really not a good housekeeper, your floors are dirty, your dishes are dirty, we recommend you get a better dishwasher, we’re going to check on you to make sure you do this correctly,’” said S. Gregory Baker, who was the head of the city’s department of public safety around the time of the Collaborative. “That’s how it was perceived within the police department.”

What’s more, police thought they had been doing a good job in the community. Yes, there were a few troubled officers, but 10 out of the 15 people who had been shot by police had pointed guns or shot at police themselves, police said. There were 50 community patrol officers in certain districts who knew what was happening on the ground, something that wasn’t done in most cities at the time.

“From my perspective, we were the leaders in community policing at that time — or at least we thought we were,” Herold told me.

In the first few years after the Collaborative, the police pushed back against change. A survey of police conducted in 2004 found that one-third of police wanted to leave the department, and that 85 percent thought that “the collaborative agreement to micromanage their jobs has been a waste of time,” according to a Cincinnati Enquirer column at the time.

In 2004, the independent monitor determined that the city was not complying with provisions of the collaborative, which constituted a material breach. The police department had barred plaintiffs from ride-alongs, denied the Department of Justice access to certain documents, publicly questioned the competence of the monitor, complained about the Collaborative, and kicked a member of the monitoring team out of police headquarters, according to the monitor.

“We walked into it very skeptical,” Streicher told me. “We didn’t think we were being treated fairly and objectively.”

In 2005, the city and the police department had to reaffirm their commitment to the Collaborative. Also in 2005, a RAND study on policing in Cincinnati found that residents of black neighborhoods were still subject to aggressive policing, traffic enforcement and pat-downs.

Meetings between the parties in the Collaborative were “unbelievably rancorous,” the monitor, Saul Green, told me. “The police and the city were extremely recalcitrant.”

It was bad enough that little seemed to have changed. But for a few years after the riots, it seemed like things were actually getting worse in Cincinnati. The Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, where Thomas had been shot, had been on the cusp of a recovery, but after the riots, it was boarded-up and once again riddled with blight. A boycott organized by community members who thought the reforms were moving too slowly caused more tensions in the city.

After the Collaborative, Cincinnati initially experienced a plague of “de-policing,” in which patrols stayed out of certain neighborhoods to avoid trouble, Baker said. Homicide and violent crime rates began to climb in 2002, and in 2006, the city had 85 homicides, which was the highest murder rate on record. Frustration seemed to be creeping into the report by the city’s independent monitor, too.

“It is highly disappointing that only a small number of the projects from this quarter contained in the Unit Commander reports reflect any familiarity with problem solving,” the monitor wrote, in December 2006. “Clearly there is a lack of oversight, guidance, coaching, and perhaps adequate training since the majority of the efforts should not be of this quality after four years of stated commitment” from the police department.

* * *

Police Officer Eric Dunn stands on a patch of green grass at the corner of Woodburn and Hewitt Avenues in the Evanston area of Cincinnati. Just a few years ago, this was one of the most violent areas in the city, a place where police sometimes had to respond 15 times a day, and where drug deals and murders were not uncommon. Across the street stood one of the city’s oldest public housing complexes, which was dilapidated and also a center of crime. On this very lot, at a store called Jacks Carry Out, a man was shot a year ago, and later died from his injuries.

This plot of grass is an example of how problem-oriented policing can change a city. When members of the Evanston community started to complain about crime in the vicinity of the store, police officers were at the meeting to listen. The data showed that the location was a place where disputes often turned fatal. They decided to minimize the number of people hanging out in front of the store, not by arresting people, but by moving a bus stop down the street and moving a phone booth further away. Then, when the store’s owner didn’t respond to requests by police to stop allowing drug deals to take place on his property, the city went after his liquor license, said Dunn, who was involved with the process. The city bought the building and tore it down, and is now seeking a developer to build a grocery store. The formerly violent corner is now transformed, because of the involvement of the community and a number of city departments, and, of course, the police.

“People talk about community policing, but they don’t have an idea of what it really looks like,” said Brickner, of the ACLU. “It wasn’t just about responding to crimes but instead hearing about the overall health of the community. Hearing about the blighted houses, where that’s contributing to poverty and crime, hearing about where young people are congregating and thinking about what kind of training is available to them.”

Many people in Cincinnati say the police finally started to buy into these reforms in 2006, after a new mayor had been elected and a new city manager appointed (Mayor Charlie Luken, who governed the city from 1999 to 2005, had asked the Justice Department to stop putting police through “this silliness,” in 2004.)

Green, the monitor, said the changes tracked very closely to new city leadership taking office. The police chief reports to the city manager, after all. New city manager Milton Dohoney Jr. started attending meetings of the parties in the Collaborative, and made sure that the rancor that had characterized them before wasn’t tolerated.

“They became much more business-like, and we were able to move forward,” Green said.

Dohoney seemed to understand that the city had signed an agreement and that it needed to come into compliance with the reforms, or face penalties, Green said.

A new attitude from people at the top made all the difference, Herold said. Police, at the end of the day, will do what they’re told. When they’re told to engage in problem-oriented policing, and are evaluated on how well they do that, their habits start to change.

Senior officers slowly started making it clear that officers weren’t going to get promoted if they didn’t embrace problem-solving and make an effort to listen to the community, Dunn said. That may be because those leaders had to answer to the independent monitor. The monitor looked closely at district reports for examples of problem-solving, held police accountable for training officers in problem-oriented policing, and constantly checked in with the Citizen Complaint Authority for police progress.

For his part, Streicher says that it only took three years or so for police to start implementing the changes. Cops on the ground started to realize that collaborating with the community made their jobs more pleasant, he said, and as the department realized problem-oriented policing was working, it started to push it more. Listening to the community helped too, he said.

“When people get the opportunity to vent and you listen, I guess it starts to sink in,” he told me. “We realize we aren’t as good as we thought we were.”

“When people get the opportunity to vent and you listen, I guess it starts to sink in,” he told me. “We realize we aren’t as good as we thought we were.”

Mike Brickner, of the ACLU, says he first realized something might actually be changing in a 2006 community meeting with police officers and members of the Collaborative. A fellow staffer reported back that community members were standing up for the police at the meeting, rather than criticizing them.

“That was one of the first times that I really felt like, ‘Oh my gosh, we really are making progress,’” he told me.

In 2007, the police department changed its sworn officer job descriptions to emphasize the role of problem-oriented policing in their work. The same year, the city and the plaintiffs of the original ACLU lawsuit agreed to extend the Collaborative one more year than was originally planned to accelerate the adoption of community problem-oriented policing. In 2008, the independent monitor issued his final report, writing that the city had made “significant changes in the way it polices Cincinnati.”

“I truly believe that there originally was a we-they mentality when it came to certain citizens,” Dunn told me, about police.

Dunn may be a good example of how the police slowly began to court and win community support. Dunn, who was deeply embedded within the community, resigned from the Fraternal Order of Police in the aftermath of the riots. In time, though, after the FOP elected a new president, and after the police department appeared to be serious about reforms, Dunn rejoined the union.

Slowly, officers who had berated Dunn and his partner Scotty Johnson for allowing community members to address them by their first names either left, or converted to the new mentality. Same with those who had called the new method of policing “hug-a-thug” or “love police.” Slowly, police officers started to tell community members exactly what was going on at a crime scene, rather than stonewalling them.

And in a contrast to the stop-and-frisk policies that have gained popularity in cities across the country, which cast the widest possible net, Cincinnati police tried to focus their efforts more narrowly, targeting the 0.3 percent of people in the city who accounted for three-quarters of the city’s murders through a program called the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence, or CIRV. Through CIRV, officers talked to the family members of the violent gang members, as well as the gang members themselves, trying to help them transition out of a violent lifestyle.

The reforms soon began to make a difference on the ground. In a county that had to reduce jail space by one-third in 2008, officials were relieved to see that Cincinnati’s focus on problem-solving was leading to fewer arrests. Felony arrests fell from 6,367 in 2008 to 5,408 the following year; by 2014, they were down to 3,735. Misdemeanor arrests fell by 3,000 between 2008 and 2009, and dropped by an additional one-third between 2008 and 2014, according to Engel, the Cincinnati professor. And in the same years, even as arrests were falling, almost every major category of crime also declined.

In New York City, by contrast, between 2005 and 2010, where stop and frisk was being implemented as policy,misdemeanor arrests increased 28 percent. The misdemeanor arrest rate jumped 190.5 percent between 1980 and 2013.

Misdemeanor Arrests in Cincinnati

“Law enforcement officials in Hamilton County learned that more arrests do not equate to increases in public safety; rather public safety is enhanced when arrests are limited and strategically focused,” Engel and co-authors wrote, in an unpublished document prepared for a recent roundtable at John Jay College.

* * *

Police and the community still struggle to maintain the changes. A new chief, James E. Craig, appointed in 2011, wanted the department to implement Compstat and do away with problem-solving. When current chief, Jeffrey Blackwell, became head of the department in 2013, he wasn’t familiar with problem-oriented policing, but has since embraced it.

“We had to fight hard to keep problem solving,” Herold told me. “Every time we have a new leader, I’m worried that it’s going to go away.”

Of course, not everything is perfect now in the Cincinnati police department. Two families filed lawsuits against police, for example, after two separate run-ins with the same police officer, whose dashcam was turned off during both encounters.

Some police officers still discriminate on the basis of race, said Dion Branhan and Mike Dodson, two black men I met near the University of Cincinnati.

“I haven't seen much of a difference,” Branhan said.

“They still need some type of cultural-diversity training,” Dodson added.

In Over-the-Rhine, the now-bustling downtown neighborhood where the riots began, black men say they’re hustled by police who don’t want them standing around on the street, even though white people are allowed to stand around outside the bars and restaurants nearby. One man I spoke to in that neighborhood, who goes by the name of Big Quartar, said he was stopped and put in the back of a police cruiser recently because he was mistaken for somebody else. Although one of the officers knew him, her partner rolled up the windows and made Quartar sit in the hot car for a long time, without explanation, he said.

“All they do is look at me with nasty attitudes,” he told me. “They do a lot of foul things.”

What’s more, he said, any policing changes since 2001 have done little to remedy economic inequality in the city. Many of the people he knows can’t find a job, even as the nearby neighborhood prospers. For all the talk of police as social-service officers, police reform can’t fix an economy that’s tougher for people at the bottom.

“People need help in the streets—they don’t need help from police,” he told me. “They can’t give you a job.”

Roley, the community activist, has the same complaints. In the aftermath of the riots, a Minority Business Accelerator was created in the city, but the black community is being pushed out of Over-the-Rhine, she said. She sometimes wonders if the police reforms are meaningful without a corresponding degree of economic change.

Cincinnati has more income inequality than any municipal area in Ohio except Cleveland, and fares worse on that measure than other similar cities, including Pittsburgh, Louisville, St. Louis and Indianapolis, said Julie Heath, the director of the University of Cincinnati’s Economic Center. The median household income in Cincinnati in 2001 was $21,000 for African Americans and $36,500 for whites, she said. In 2013, the median household income for African Americans had only gone up a few hundred dollars, to $21,300, while white median income jumped to $48,000 in Cincinnati.

In some ways, though, the widening of the gap between the rich and the poor makes Cincinnati’s police reforms in the years since 2001 even more impressive. In a city in which incomes diverged and in which residents had ample reason to stay angry with police, residents and cops instead ending up working together.

By 2009, when RAND conducted a lengthy, data-driven report on how policing in Cincinnati had changed since the Collaborative, it concluded that relations were improving. Black residents surveyed perceived greater police professionalism in 2008 than in 2005, and less racial profiling in the later year. Crime was decreasing at the time of the report, and, according to RAND, “police-community relations in Cincinnati have improved in a number of ways.”

Officer Dunn sees that improvement when he sets foot on the street, or helps walk kids home from school, or engages in problem solving with the community. Or when he visits Evanston, where residents know him by name. As Dunn, Johnson and I talked in front of the area where Jack’s Carry Out had been located, an older black woman came striding towards us with purpose.

“You’re supposed to stop over there, every time,” she said, jokingly, to Johnson, who no longer is on patrol in the area. Then she gave him a big hug.

She is Anzora Adkins, president of the Evanston Community Council, a revitalization group. She has lived in Evanston for 45 years, and has seen it go from a middle-class neighborhood to an area with one of the city’s highest crime rates. Now it’s on its way back up, she says, in no small part because of the collaboration between police, her council, and other city departments.

“In any group or situation, communication is key,” she told me.

* * *

Cincinnati’s reforms won’t be easy to replicate in other cities. Each time I asked a participant in the Collaborative about whether other police departments could follow Cincinnati’s lead, I got the same answer: Probably not without a Justice Department order to do so.

“I think it's very hard,” Mayor John Cranley told me. “It's a combination of carrots and sticks, and the Justice Department is a pretty big stick.”

Police departments may adopt some principles of problem-oriented policing, but it’s much easier to just continue policing as they always have, Herold said. Without a document like the Collaborative to refer to whenever an issue arises, departments will likely move onto the next fad, said Eck, the criminologist. And without city money to train police officers, hold community meetings and pay an independent monitor, it will be difficult for police to change.

“Reality tells us that it does not occur without this federal intervention,” said Streicher, who now consults police departments trying to reform. “You can very easily slide back into the same problems and issues you had in the past, unless your feet are held to the fire and the person you’re answering to is a federal judge.”

A Justice Department investigation also brings with it a mandate for resources. The city spent more than $20 million to implement reforms, Streicher said, and in an era of cash-strapped municipalities, it’s very unlikely that any city would spend that much on police reforms without a legal requirement to do so.

Even if other cities did have the funds to implement reforms, and the Justice Department compels them to do so, it won’t happen overnight. Iris Roley remembers feeling furious when a monitor told her change would take 10 years. He ended up being right, she said.

It’s unclear whether some of the state-wide mandates could be enough incentive for departments. After Ohio’s Task Force issued its report last month, Governor John Kasich created a permanent standards-writing body that will make recommendations for police departments in the state. When police departments meet those standards, which include training officers in problem-oriented policing, they’ll get certified by the state, said Joe Andrews, a spokesman for the Ohio Department of Public Safety.

Whether that will be enough to mend relationships with torn communities remains to be seen.

“Everyone breathes a sigh of relief when consent decrees are signed,” Green, the monitor said. “But that’s when the work really starts.”

But even if other departments don’t adopt the reforms undertaken in Cincinnati, the city seems determined to continue on the problem-solving path, 14 years after the shooting of Timothy Thomas. Other cities that implemented problem-oriented policing, including San Diego and Charlotte, later abandoned it when new leadership came into the police department, criminologists told me. Eck, the professor, says that Cincinnati built a constituency of people within the police department and public who will constantly remind new officials that the city is dedicated to problem-oriented policing. Leaders’s dedication to maintaining the Collaborative is unusual, observers say.

Mayor Cranley says that as long as he’s around, he’ll make sure the police adhere to community problem-oriented policing. He was elected in November of 2013, and had been the head of the public-safety subcommittee on the City Council at the time of the riots.

“As long as I’m here, I’m going to keep it,” he told me, about problem solving. “I was here the last time, and we do not want to go back to that.”

If Cincinnati is unique in its decision to adopt problem-oriented policing on a citywide basis, it is even more unique in its dedication to maintaining the strategy more than a decade after the riots. People there have pushed hard for the Collaborative through three mayors and three police chiefs, and some seem even more dedicated than ever to prove that a partnership between police and the community is the best form of law enforcement.

There’s inequality throughout the country still, and there’s still police brutality and a growing problem with incarceration. But in Cincinnati, a diverse group of people, including police officers and citizens, are trying to understand one another. That’s led to fewer arrests, fewer people in jail, less crime, and more dialogue between police and the community that pays them to do their job. For a great many other cities, Cincinnati’s imperfect present provides a glimpse of a much better future.

Alana Semuels is a former staff writer at The Atlantic.